Do you really need to vote?

It sounds like a no-brainer. The answer seems so obvious. However, in the age of information it is important to verify the intentions behind the uses of language that seem obvious. While there are many examples that I could conjure up, I will leave some of these “no duh” statements for future installments of this series of posts.

A question like “Do you really need to vote” is quite similar to a question like “Do you really need to tip your waiter” in that the answer most will give is “Yes, of course” while a minority would say “Well you technically shouldn’t have to, but you probably should.” It’s pretty difficult to find someone who would give a blanket “No, you shouldn’t”, because discouraging political activity often has selfish motives behind it. Mix in the fact that voting is definitely the single, most effective way to have your voice represented in government and the message of “Get out and vote on November 3rd!” is an honest, bipartisan message to share.

In a utopia, where information is free, it costs a negligible amount to vote, and voters are aware and educated on the happenings of elected officials and agencies, then maybe the conversation should just stop there. I think that since the real world is very different from the ideal, it is perhaps worth it to analyze what voters would act like in this thought experiment.

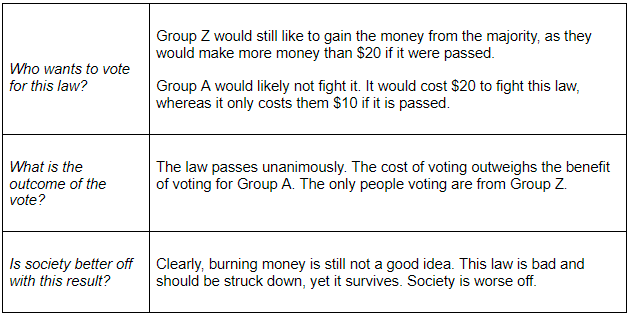

Suppose there is a law where we take $10 from everyone with a last name that starts with A-Y, burn half of it, then give whatever remains to the people with a last name that starts with Z.

We’ll call the majority “Group A” and the minority “Group Z”. Here’s the result of the thought experiment.

This is ideally, how a democratic society would work. The system is good, so far.

One aspect, that many do not consider politically is the cost of voting, and also the cost of gathering information about how to vote. I felt through the screen wince at my implication above that I implied the cost to vote or get information was not negligible. This is because (as mentioned in the intro of Necessary Lies), time and energy is a resource that is expended all the time. It may not cost any money to vote, but it certainly does cost something to:

Be aware of a pending vote

Figure out what is being considered

Read and decide if it is good or bad idea for you to support this idea

Get up, get out, and vote

This time and energy can represented in monetary units, so for the sake of example, lets say this “voting cost” is $20 and return to our previous example above. That is to say, the same law will try to pass, but to vote at all, it is required to pay up $20. Here would be the result of the experiment with this cost added in.

This is an example where not voting in a direct democracy was the most economical solution for both groups, and yet it creates legislation that is objectively bad. There are many examples where the voting cost being high causes this sort of objectively bad legislation to take place.

One such example would be the tariff on sugar. These artificially raise the price of imported sugar into the US to give an advantage to US sugar producers. The majority of people are not tuned into the issue of whether or not their Senator votes for sugar tariffs, but a minority of sugar producers (who stand to gain a lot if these pass, hello Group Z) care hugely and influence officials to pass the legislation. Long story short, tariffs create a deadweight loss (benefitting the government), but it would cost the general public (Group A) much more than what they stand to gain by fighting sugar tariffs. So these bad laws exist.

These examples create rational ignorance. This is an incentive to remain ignorant and disengaged from the voting process, by using the legitimate rationale that voting cost is too high for the benefit of voting to shine through.

But we live in a republic!

Republics lower the cost of voting by basically hiring someone else to study legislation. This person is a representative. This November, ALL 435 representatives in the House are up for election. While voting for a representative to handle legislation drastically lowers the voting cost (versus voting on every issue), it comes with a sleuth of problems. Gerrymandering, the issue with how district lines are drawn that has a large influence with how “safe” elections are, (having few battleground districts per state is attractive as a policymaker) is probably one you have heard already. The direct democracy fault, mentioned in the thought experiment above, still exists, though.

How a representative thinks

A policymaker has stakeholders. There are people relying on the performance of them in order to get some sort of action out of them. A lot of the time, those in government are seen as “public servants”, and I say that there still is an aspect of being a politician that involves doing what is best for the public.

At the same time, though, your stakeholders may not fit the demographic that reign over.

Politicians do not have to appeal to everyone.

Politicians do not try to appeal to everyone.

Politicians seek the support of the largest communities who vote.

This seems like common sense, but digging a bit deeper, it makes sense as to why so many feel disenfranchised in the United States. There are two candidates that have a serious chance of getting elected (thanks to the antiquated first past the post voting system), and so it is a race between two members of the public to be the voice of the abstract hodge-podge of ideas that a political party makes. Individuals may not fit the description of a political party easily, but activists will seldom vote for individuals.

Instead, they vote for a letter.

There’s not really a problem with the voters here, though. Voting ought to be seen as a protected form of expression. There’s limitless reasons as to why people can vote for whoever they wish. It can be as fact-based or as arbitrary as desired. In the end of the day, the economics of voter behavior makes sense. People will do what they, personally, believe is right. The systems we have placed have one goal, to solve problems by conversing with people, who often have other viewpoints.

If you are (still) here, then you may not have a strong political identity that aligns with a person running for office. What should you do? Make a character judgement as your vote? Perhaps. Vote based on a single issue or subset of issues that are most important to you? Sounds good to me.

Do you really need to vote?

Well, yeah. I wouldn’t fall into the “with us or against us” trap that so often plagues this discussion. “If you don’t vote, then you’re really voting for X to be elected” This statement is obviously misleading. I would argue that it is important to have your voice heard in public policy, as the government is an extension of the private person. If the government does something, well, there’s a paper trail that will tell you whose idea it was. There has to be (and that gets into the fourth branch of government, but I will get to that later probably).

Unfortunately, the problem (and beauty) of voting is that one person gets one vote. A high quality, well thought out vote is the same as someone who marks next to a letter every year.